THE FINAL MOMENT BEFORE TRANSFORMATION: THE HUMAN AT THE THRESHOLD BETWEEN BODY AND TECHNIQUE IN ‘KAMEN RIDER’

This essay investigates Kamen Rider, the Japanese superhero media franchise, as a myth read through the lens of philosophy, in which the human body—crossed by technique—becomes the central site of ethical and political dispute in contemporary Japan.

Prologue – What Does Kamen Rider Mean?

To understand the object of this essay, it is necessary to answer precisely what Kamen Rider is and why it occupies a singular place in Japanese culture. The franchise is part of the tokusatsu (特撮) genre, an abbreviation of tokushu satsuei, or ‘special filming’, a term used for Japanese productions that rely heavily on practical special effects, costumes, and stunt work. As Brown (2010, p. 22) notes, tokusatsu constitutes ‘a technological theatre in which the heroic body and the monstrous threat function as visual metaphors of sociotechnical tensions’.

Created in 1971 by Shōtarō Ishinomori, Kamen Rider (仮面ライダー, ‘Masked Rider’) presents a simple and enduring structure. A human being is altered by technology—biological, mechanical, or digital—and uses a transformation belt (driver) to change form with the command Henshin! (‘transformation’). Ishinomori describes the hero as ‘a violated body that decides not to repeat violence’ (Ishinomori, 1971, p. 4), a sentence that synthesizes the ethical DNA of the franchise. Since its television revival in 2000, Kamen Rider has followed a rigid industrial rhythm: one new series per year, broadcast on Sundays within the Super Hero Time block.

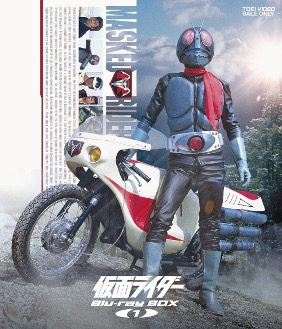

Fig. 1 — Kamen Rider Ichigō (1971), original Shōwa-era Rider.

Promotional image of the first Kamen Rider created by Shōtarō Ishinomori, marking the emergence of the technified body as biopolitical object and ethical agent within postwar Japanese culture. Source: Kamen Rider (1971–1973), Toei Company. Image via IMDb.

Gordon (2013, p. 289) observes that the Japanese imperial eras—Shōwa, Heisei, and Reiwa—‘function as mental frameworks of their time’, and fans adopt this same division spontaneously to organize the generations of Riders.

The cultural significance of Kamen Rider lies in its deep relationship with post-war Japan. Agamben (2010, p. 9) argues that the twentieth century transformed the human body into ‘a field of technical and political experimentation’, and it is precisely this historical wound that the series dramatizes. Secret laboratories, technoscientific sects, and bodies transformed against their will are the fictional stage for this tension.

During the Heisei Era, marked by the economic crisis and the ‘lost decade’, Riders begin to embody fragmented subjectivities. Galimberti (2006, p. 47) notes that in the age of technique, ‘the human being loses its former places of meaning’, a diagnosis the franchise translates into fiction: manipulated memories, and divided identities. In the Reiwa Era, the arrival of artificial intelligence reshapes the scenario. Kamen Rider Zero-One introduces the HumaGears, social robots, dramatizing the dilemma described by Han (2021, p. 15): ‘Digital society produces new forms of power that escape human control’. For this reason, Kamen Rider functions as a cultural seismograph, registering the real tensions of Japanese society—industrialization, economic crisis, precarity, algorithms—and translating them into accessible television language. The object examined here is a symbolic device that, for five decades, has dramatized the conflict between body and technique in Japanese modernity.

The Shōwa Era – The Body as Territory of War and Biopolitical Exception

The Shōwa Era (1926–1989), marked by the reign of Hirohito, concentrates the tragic arc of modern Japan: accelerated militarization, the Second World War, the atomic devastation, and the subsequent industrial reconstruction. The body, in this context, was a strategic resource, an industrial tool, and an object of technical control. Foucault (1987, p. 135) details this phenomenon as biopower, ‘the political investment of life’, which transforms the body into administrable matter. It is in this historical climate that Ichigō, Nigo, V3, X, Amazon, and others emerge.

The narrative repeats an almost ritualistic pattern. A young person is kidnapped by a pseudo-scientific organization (generally Shocker, whose name in Japanese evokes the idea of trauma), undergoes biotechnological alteration, and is converted into a living weapon. In short, the body becomes a project. Agamben provides the key to reading this violence: the suspension of the ordinary order creates a space where the human can be manipulated without limits, the state of exception. The body emerging from this space is bare life—‘life exposed to another’s will, without legal protection’ (Agamben, 2010, p. 12). The Shocker laboratory, an isolated, subterranean, and secret structure, is literally this micro-state where ethical and social norms are suspended in the name of a technical goal.

The first Rider, Takeshi Hongō (Ichigō), a university student, is kidnapped for his exceptional intelligence and physique, making him the ideal candidate for conversion surgery. He is a classic example of bare life: a subject stripped of rights and reduced to his biological and technical value. His enemies, the mutant monsters (Kaijin), are also products of this same regime of violence, bodies that either failed or were finalized in the Shocker project, but remain under the total control of the dispositif. Kamen Rider V3, which succeeds the original, intensifies this notion, with the protagonist Shiro Kazami being transformed after a devastating attack by Shocker, becoming the ‘third’ Rider, a rescue body that exists only because of the initial trauma.

The revolt arises the moment the programming fails. Hongō escapes the operating table before the final brainwashing is complete. Agamben (2010, p. 44) describes profanation as ‘removing something from its separated use and returning it to common use’. The Rider does exactly this. He takes the technique (the Cyclone, his motorcycle’s engine; the cybernetic armor) intended for domination and converts it into a weapon of protection, returning to the world what was destined for violence.

Simondon (2005, p. 27) helps us understand this process in an ontogenetic key: ‘the individual is not substance, but a process of individuation’. The Shōwa Rider’s individuation is interrupted and kidnapped, but the subject finds a breach to reclaim his own formation, redirecting the technical flow. The central philosophical dilemma is, therefore: Who controls my body—and what do I do when I discover that someone tried to programme it?

Henshin assumes a deep symbolic force here. It is the instant in which the violated body transforms trauma into responsibility. The cry does not just mean ‘transform me’; it is an affirmation of autonomy: ‘I assume the form that was imposed on me, but I redirect it toward another end’. The Shōwa Rider is the survivor who has profaned technique and returned himself to the world.

The Heisei Era – Trauma as the Substance of Subjectivity

The Heisei Era (1989–2019), corresponding to the reign of Akihito, marks a shift in the Japanese affective climate. The collapse of the speculative bubble and the ‘lost decade’ produced not just an economic crisis, but a crisis of meaning. Gordon (2013, p. 302) describes the period as ‘an era in which the future ceased to seem guaranteed and became a burden instead’.

The return of Kamen Rider with Kuuga (2000) signals this change. The enemy is no longer the totalitarian caricature of Shōwa. Evil now manifests in the fragmented world, violent and saturated with uncertainty. The Heisei hero is a wounded subject, carrying guilt, gaps, and fractured memories. He fights what time has made of him.

Umberto Galimberti (2006, p. 17) argues in Psiche e Techne that, in the age of technique, ‘technique has taken the place of the soul’, replacing the traditional anchors of meaning (myth, religion) with protocols, procedures, and routines. The result is a subject who lives in a hyper-organized world but is internally hollowed out. The Heisei Era translates this diagnosis into the hero’s figure:

- Kamen Rider Agito (2001) deals with dormant genetic powers and the struggle for identity and memory in a world where human agency is tested by superior entities and the very status of being human is contested. The protagonist, Shouichi Tsugami, suffers from amnesia, symbolizing the loss of historical and personal anchoring that characterizes the era.

- Kamen Rider Ryuki (2002) presents a Battle Royale where Riders fight in a Mirror World. This is an explicit metaphor for capitalist competition and the fragmentation of the self into multiple identities (vent decks), where technique (the card deck) is a Faustian contract for survival, reducing the life of the other to a means.

- Kamen Rider Faiz (2003) focuses on the Orphenochs, beings rejected by society who nonetheless feel and suffer, embodying the conflict between what the body is (monstrous) and what the subject feels (human). The transformation technology is a secret key, accessible only to modified bodies, raising the question of who has the right to be ‘human’ or ‘hero’.

- Kamen Rider Build (2017) resets Japan’s history, dividing the country and rewriting memories, materializing the psychic fracture of the era, where identity is malleable and manipulable by techno-political interests.

Fig. 2 — Kamen Rider Ryuki (2002): battle royale in the Mirror World.

Promotional still of Kamen Rider Ryuki, a Heisei-era Rider whose battles in the Mirror World stage the fragmentation of subjectivity and the competitive logic of late capitalism discussed in the article. Source: Kamen Rider Ryuki (2002–2003), Toei Company. Image via DCInside.

The axis of the battle shifts: it is no longer physical capture, but psychic pressure. Galimberti (2006, p. 41) warns that when technique becomes an environment, ‘the human being loses the measure of themself, because the measure becomes technique’. The Heisei Rider attempts to reconstruct an interiority in a world that has torn it apart, fighting against what they have become. The philosophical question changes: What has the technified world made of me—and how do I avoid reproducing this violence in others?

The era’s transformation devices—belts, gashats, drivers—cease to be mere equipment and become Bernard Stiegler’s pharmakon (Stiegler, 2011, p. 92): remedy and poison simultaneously. They amplify, but threaten; heal and wound. The Heisei hero must deal with the pharmakon not only in the body, but in the soul. His struggle is biological, technical, but fundamentally emotional and ethical.

The Reiwa Era – Ethical Post-Humanism and Algorithms

The Reiwa Era (2019–) places us before a new scenario: the question is not just about the body or the soul, but about what it means to be human in an environment of artificial intelligence, platforms, and algorithms.

Kamen Rider Zero-One (2019), the first Rider of this era, focuses on the HumaGears, assistance robots that learn and coexist with humans. They occupy a liminal position that can be read as a new state of exception. They exist in a state of vulnerability, depending on authorization protocols and capable of being shut down or hacked at any moment. They are liminal lives, always on the verge of being treated as mere objects.

The narrative inverts the tension. Instead of asking if machines are evil, the series questions our responsibility toward the systems we create. Aruto Hiden (Zero-One) fights to prove that coexistence with AIs is possible without reducing the parties to mere resources. If a HumaGear becomes violent (Magia), this reveals less an alleged violent essence of the machine and more the violence it learned through observation and training in our world.

Rosi Braidotti (2013) is relevant here, as the human is no longer an isolated individual, but a node in a network that articulates humans, machines, and data flows. The Reiwa Rider is the attempt to be post-human without ceasing to be ethical. He accepts the interconnection, but insists on responsibility.

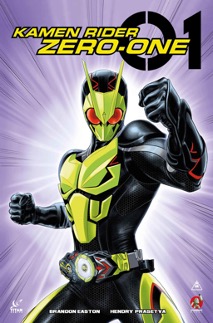

Fig. 3 — Kamen Rider Zero-One (2019): the ethical post-human.

Promotional image of the first Reiwa-era Rider, whose narrative centers on artificial intelligences (HumaGears) and the redistribution of agency between humans and machines. Source: Kamen Rider Zero-One (2019–2020), Toei Company. Image from Comic Book.

The problem of algorithmic governance deepens in Kamen Rider Geats (2022), where life turns into a survival game (Desire Grand Prix). The participants’ lives are literally reduced to scores and rewards, administered by a complex algorithmic system (the GM, Game Master). The series dramatizes Byung-Chul Han’s thesis (Han, 2021) that we live under an invisible layer of algorithmic decisions that classify, catalog, and determine our social value and even our existence. Geats shows that technique now manages not only the body (like Shōwa) or the soul (like Heisei), but the very structure of social reality, turning precarity into competitive spectacle.

The henshin of Reiwa is, therefore, the leap from the centered human to the responsible human—someone who accepts that they are no longer the center, but who must answer for the consequences of the technique they initiated.

Case Study: Kamen Rider Black – The Programmed Body

Kamen Rider Black (1987) and its successor, Black RX (1988), emerge in the final years of the Shōwa Era, at the height of the economic miracle, but with a diffuse malaise: the sense that technique is advancing faster than humanity’s ability to guide it. The series becomes a cultural phenomenon, transforming the adopted brothers, Kotaro Minami and Nobuhiko Akizuki, into symbols of a generation whose futures were administered by external forces.

The kidnapping and mutation of the brothers by the Gorgom cult constitute the core of the Agambenian state of exception. The youths are reduced to bare life and biotechnological resources. Nobuhiko, transformed into Shadow Moon, represents the body that cannot escape. He is pure function, the ‘human transformed into function’ described by Galimberti (2006). He is not evil; he is the result of the technique that confiscated his interiority. The difference between Kotaro and Nobuhiko is not moral, it is chronological: one awakened before the programming was finalized, the other awakened too late. Kotaro, the Rider, becomes the profaner of technique, while Shadow Moon, the enemy, is the perfect product of the dispositif.

This problem resonates deeply in Black RX, when Kotaro is captured again and transformed by the Crisis Empire. The repetition of trauma, and the second transformation, raises the question: can a body that is continually reconfigured by technique still consider itself autonomous? The emergence of RX, an even more cybernetic and powerful form, suggests that ethical agency lies in the subject’s will, not the purity of their body.

This question returns in Kamen Rider Black Sun (2022), which revisits the tragedy in the Reiwa context, marked by polarization and identity crisis. The myth is displaced: the kaijin (the monsters) are explicitly oppressed minorities. The Century King Project (the new version of the ritual) is a nationalist agenda. Medical technologies are instruments of political control. The violence is not merely biological; it is administrative and algorithmic.

Agamben becomes literal: the kaijin are monitored in camps, registered as administrative categories—lives reduced to a permanent state of exception. Han and Galimberti unite here: the body is classified and monitored by a propaganda system and fear, where technique replaces political imagination.

Fig. 4 — Kamen Rider Black Sun (2022): re-reading of the programmed body.

Promotional image of Kotaro Minami and Nobuhiko Akizuki in the Reiwa reinterpretation of Kamen Rider Black, staging the conflict between profanation and total technical capture. Source: Kamen Rider Black Sun (2022), Toei / Prime Video. Image via Toy-People.

The series reveals that the story of Kotaro and Nobuhiko was always an allegory of programmed bodies and administered lives. What changes is the technical environment: from an industrial imaginary (Shōwa) to an informational and algorithmic imaginary (Reiwa). Black is, in all its versions, the philosophical figure of the body that refuses to be only function.

Tojima – The Will to Act

Tojima (from the film Tojima Wants to Be a Kamen Rider) embodies the civilian who lives on the threshold between the ordinary and the extraordinary. He is the fan who desires not power, but meaning—the structural deficit of the contemporary world, where “the coherence of meaning dissolves in the multiplicity of performance” (Han, 2021). The Rider, for him, is the event of presence, someone who acts when the world hesitates.

Tojima’s desire confirms Haraway’s thesis (Haraway, 2009): “the myth of the hero tells us more about our own desires than about the deeds of heroes”. He sees in the masked hybrid the possibility of a human who rejects the function of a passive spectator, which is imposed by the modern world. If the Rider is the body that resists technique, Tojima is the heart that resists apathy.

His philosophy is one of ethical inclination. When Tojima says “I want to be a Kamen Rider,” he is rejecting the invisible function the world tries to impose on him: that of a replaceable part, of a passive existence. He wishes to exercise what all Riders, since 1971, remind us: action is a choice. Tojima’s tragedy is that his only weapon is his will, but his will is what makes him, ethically, a Rider.

The Final Moment Before Transformation

Kamen Rider is, ultimately, the narrative of a human being who, even surrounded by dispositifs of power and technique, insists on clinging to a spark of decision amidst the automatism of the world.

The Shōwa Rider is the body that profanes technique and rejects bare life. The Heisei Rider is the subject who struggles to reconstruct interiority after technique replaces the soul. The Reiwa Rider is the ethical post-human who accepts coexistence with AI systems but assumes responsibility for the consequences.

The core of the franchise lies in the word Henshin. Transforming does not just mean changing form; it means changing one’s position toward the world. The true human henshin occurs one second before the physical transformation, when someone decides to be a cause, and not just an effect, of their own history.

Fig. 5 — Kamen Rider Black (1987): the moment of transformation.

Promotional still from Kamen Rider Black, illustrating the instant of henshin as the liminal passage between the human body and its technified form. Source: Kamen Rider Black (1987–1988), Toei Company.

It is at this precise point, at this final moment before transformation, that Kamen Rider establishes its true significance: an enduring narrative that stages the philosophical conflict between automated function and human will.

References

Agamben, Giorgio. Homo sacer: o poder soberano e a vida nua I. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 2010.

Braidotti, Rosi. The posthuman. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013.

Brown, Steven T. Tokyo cyberpunk: posthumanism in japanese visual culture. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Foucault, Michel. Vigiar e punir: nascimento da prisão. 20. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1987.

Galimberti, Umberto. Psiche e techne: o homem na idade da técnica. São Paulo: Paulus, 2006.

Gordon, Andrew. A modern history of japan: from tokugawa times to the present. 3. ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Han, Byung-Chul. Sociedade do cansaço. 2. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2015.

Han, Byung-Chul. Infocracia: digitalização e a crise da democracia. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2021.

Haraway, Donna J. Manifesto ciborgue e outros ensaios: ciência, tecnologia e feminismo-socialista no final do século XX. 2. ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2009.

Ishinomori, Shōtarō. Kamen rider. Tokyo: Ishimori Productions, 1971.

Japan National Diet Library. The japanese calendar. Tokyo: National Diet Library, 2019.

Simondon, Gilbert. L’individuation à la lumière des notions de forme et d’information. Grenoble: Éditions Jérôme Millon, 2005.

Stiegler, Bernard. A técnica e o tempo 1: o falso início. São Paulo: Estação Liberdade, 2011.

Kamen rider (1971–1973). Dir.: Shōtarō Ishinomori; Toei Company. TV series.

Kamen rider black (1987–1988). Dir.: Yoshiaki Kobayashi; Toei Company. TV series.

Kamen rider black rx (1988–1989). Dir.: Yoshiaki Kobayashi; Toei Company. TV series.

Kamen rider black sun (2022). Dir.: Kazuya Shiraishi; Toei / Prime Video. TV series.

Tojima wants to be a kamen rider (2025). Dir.: Ryuta Tasaki; Toei Company. TV series.

Kamen rider kuuga (2000–2001). Dir.: Takuya Yamaguchi; Toei Company. TV series.

Kamen rider faiz (555) (2003–2004). Dir.: Ryuta Tasaki; Toei Company. TV series.

Kamen rider w (2009–2010). Dir.: Koichi Sakamoto; Toei Company. TV series.

Kamen rider gaim (2013–2014). Dir.: Ryuta Tasaki; Toei Company. TV series.

Kamen rider build (2017–2018). Dir.: Ryuta Tasaki; Toei Company. TV series.

Kamen rider zero-one (2019–2020). Dir.: Teruaki Sugihara; Toei Company. TV series.

Kamen rider revice (2021–2022). Dir.: Takayuki Shibasaki; Toei Company. TV series.

Kamen rider geats (2022–2023). Dir.: Teruaki Sugihara; Toei Company. TV series.

X.