ECHOES OF WAR CRIES: VIETNAM’S SONIC WAR AGAINST COVID-19

VIETNAM AND LOUDSPEAKERS

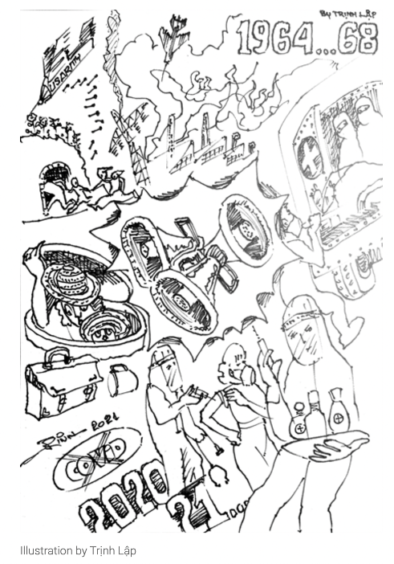

COVID-19, a once-in-a-century global event, shattered any illusion of disease boundaries. Despite efforts to contain the virus in Wuhan, it swiftly spanned the globe, leaving no area untouched—including neighboring Vietnam. The pandemic challenged societal norms and tested nations worldwide, reshaping lives and daily interactions. Vietnam, as well, felt the urgency, leveraging extensive media to convey vital COVID-19 updates, akin to a wartime call to action. However, unlike countries with advanced medical facilities like South Korea or China, Vietnam could not afford expensive mass testing equipment and vaccines at the time. Thus, it relied on the cooperation of its citizens to combat the pandemic. The country back then implemented a messaging propaganda campaign in posters, slogans, mass media, and loudspeaker systems, which is in sites that people encounter everywhere in daily life.

The country’s officials made use of the public-address systems (loudspeakers) to disseminate information of the impacts of the virus, deploying the rhetoric of war to evoke collective solidarity and to call for the people’s compliance. The media propagated the discourse of fighting the virus as an invisible enemy, using war imagery to unite the state and its citizens. The slogan “Fighting against COVID-19 pandemic as fighting against invaders,” which was first mentioned by Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyễn Xuân Phúc at the start of the national containment campaign, has immediately found resonance among the public, the authorities, as well as the news media. Since then, it has been widely used by political leaders, reporters, and anchors in public health communication. Other slogans from the loudspeakers sound out, “Every citizen is a soldier in the fight against COVID.”

Together with quick prevention and communication, the disciplining efforts through the media of the Vietnamese state by using war imagery in the slogans proved to be effective in attempts to ensure the national lockdown. Reportedly, on June 8, 2020, after Vietnam successfully returned to its former state without any detected cases of community spread of the coronavirus, the Vietnamese Prime Minister made a speech highlighting Vietnam’s triumph over COVID-19 and drawing a comparison between the country’s significant success in handling the pandemic and the victory in the Vietnam War in 1975. He then did not hesitate to contrast Vietnam’s success with the perceived failure of Western nations, particularly the United States, in managing the virus. In a striking remark, he expressed: “if the utility poles in the US had legs, they would now be going to Vietnam.” Vietnamese media on the same day simultaneously quoted his statement and expanded: “In the past, after 1975, people for a long time would say: “If the utility poles could walk, they would all run to America.” And in reality now, in the United States over the past few months and many other countries, “If the utility poles in the US could walk, they would return to Vietnam.” The statement establishes a juxtaposition between Vietnam’s remarkable success and the United States’ simultaneous struggle with the devastating impact of the pandemic and widespread national protests. It proceeds to evoke the aftermath of the historical war between the two nations, reminiscent of the experiences of Vietnamese individuals who sought refuge in the US following the events of 1975. This statement, expectedly, was removed from all the national newspapers on the same day, after much unease in Vietnamese social media platforms and international media.

In Vietnam, a customary fixture found atop a utility pole is usually a loudspeaker, resounding authority’s messages throughout the surrounding neighbourhood at 6:30 a.m. and 4:30 p.m. on a daily basis. It was originally employed in the 1960s to transmit warnings of American bombings and the government’s messages and was recently regarded as an “urban nuisance and a representation of ideological conservatism” (Võ, 2017). The reincarnation of the loudspeaker system by the authority in accordance with the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak enables it to persist in its role during the ongoing “war against COVID-19.” The juxtaposition of the seemingly outdated loudspeaker system with contemporary practices such as Facebook updates and smartphone messaging seems to signify the willingness of the government to embrace novel digital technologies while remaining committed to upholding their vintage heritage.

To explain this “retro” option, Vietnam’s colonial history unfolds an intimate relationship with radiophonic technology. During the mid-20th century, loudspeakers were integrated into broadcasting stations across villages and urban areas, forming local public announcement systems. These systems were further linked to broadcasting stations at the county level, creating an extensive wired broadcasting network throughout the country. The turbulent times of the War of Independence (1946-1954) and the Vietnam War (1955–1975) imposed specific demands on broadcasters and their audiences. Vietnamese state media underwent significant transformations in response to political transitions, utilizing broadcasted sound to shape people’s perceptions of national identity, unity, and political ideology. The act of sonic demarcation from above paralleled the voice echoing from supreme leaders to the united populace, blurring the boundary between the living and the dead and making the absent painfully present. This strategy, as theorized by Murray Schafer, can be seen as an existential echo, where a person with a loudspeaker possesses greater dominion over acoustic space, emphasizing the power dynamics involved (Schafer, 1993, p. 77). Ultimately, the most potent sonic weapon is the one that mobilizes and empowers a population, inspiring them to fight and unite the nation.

FIGURE 1. A US PSYOP SOLDIER STANDS WATCH AS AN ARVN SOLDIER BROADCASTS A SURRENDER APPEAL THROUGH A LOUDSPEAKER

Since its resurgence in 2020, the dissemination of loudspeaker broadcasts has become a regular occurrence in urban areas, reaching the public on a daily basis. Amidst the eerie silence of absence, these broadcasts intersected with the clamour of ambulance sirens, checkpoints, and enigmatic sounds emanating from military-controlled facilities where mandatory quarantine was enforced.

The significance of sound and its associated technologies in the realm of politics, serving as a demonstration of power within society, becomes evident in various circumstances and political events. According to Attali, sound, particularly in its noisy manifestation, operates as a disruptive force, an unmistakable agitation that announces violence perpetually directed towards the social order. From this perspective, the introduction of asymmetry through the loudspeaker, which transmits unidirectional sound, introduces a novel dynamic of acoustic power. The impact of this technology appears to compress the spatial dimension that typically separates and segregates us, introducing a discourse of “speaking at a distance” (Attali, 1985, p. 60). As Attali points out, Hitler’s assertion in a 1937 German Radio Manual that “without the loudspeaker, we couldn’t have conquered Germany” epitomizes the transformative effect of amplified voices in public addresses, fundamentally altering the nature of authoritative vocalization (Attali, 1985, p. 87). Through the loudspeaker, authority can assert its presence from a distance, engage in address without being addressed in return, and exert dominance through sheer volume.

SOUND AND POWER: A DIALOGUE BETWEEN FOUCAULT AND DELEUZE

I believe that staging an encounter between biopower by Foucault and affect by Deleuze is to bring together two ways of substantial thinking about the relationship between power and life, between sounds and language. And it is relevant in this context. Regarding loudspeakers, biopower manifests through the language used in the slogans, operating the affective state and regulating the awareness of listeners, as loudspeakers can create a sense of urgency and immediacy that mobilises people into action. Aligning with this inquiry, Deleuze’s non-representational theory emphasises the ways in which power operates through the modulation of affects and pre-personal intensities, taking sound beyond its intended purpose of conveying meaning. In this context, non-representational theory can help us understand how the affective qualities of sound, such as echoes, intensity, and vibrations, can shape one’s bodily experience and responses.

The audible slogans from loudspeakers that emerged among the transformed soundscape can be seen as a tool of biopower. The first pole of biopower, known as anatomo-politics or disciplinary power, was extensively analysed by Foucault in his earlier work, “Discipline and Punish” (1975). The second pole, referred to as biopolitics, focuses on the subjectification of the body. In a nutshell, the second pole, biopolitics, is the study of governing strategies focused on the regulation of populations and the management of “life itself.” Foucault developed his ideas on biopolitics in the 1970s in a series of books and lectures, covering a myriad of contexts under which the exercise of discipline and biopower could be observed. The pivotal year of 1976 played a significant role in shaping the foundational idea of biopolitics. It is noteworthy that Foucault delivered his lectures during the same period when he was in the process of completing his influential work, “The History of Sexuality” (1976).

Biopower operates in a shift from those in power to population and territory by addressing the key question of how to control groups of people as living bodies. Biopower works through both the individual and the species, as control is centered on individual bodies through training of docility and utility and on populations through the management of procreation, health, and mortality, as well as the introduction of patterns of normativity and deviance. In a population, bodies are assigned different values in a relative logic of calculating, measuring, and comparing, and a biopolitical calculus is in place that determines who gets to live and be cultivated for labour and (re)production and who is left behind to die.

Regarding the government’s decisions to voice the “war imagery” (such as the “war against the virus”) and characterize the coronavirus as an “invisible enemy,” it is noticeable that the tactics deployed against the “danger” constituted by the narrative of fighting the pandemic served to impose security apparatuses. With the spread of COVID-19, the governed are urged to adhere to a biopower that promotes obedience and voluntary servitude. It is this “war” that seeks to be both brought about and made invisible by governmental strategies.

Deleuze emphasises the idea that sound is not simply a physical phenomenon but a complex and dynamic relationship between different elements, such as technology, bodies, and the environment. In Deleuze’s sound studies, the focus is on the relationships and resonances between different sonic elements. He embraces non-representational theory and emphasizes the transformative potential of sound as it encounters other modes and enters into composition or decomposition. These encounters generate affective events, where the intensities and capacities of the involved bodies interact and give rise to new sonic configurations. Deleuze’s sound studies focus on the ways in which sound creates and transforms social, cultural, and political contexts. This perspective acknowledges the interplay between sound and its spatial, historical, cultural, and aesthetic dimensions. He highlights the importance of understanding the specific sonic environments in which sounds are produced and received and the ways in which these environments shape our perceptions and experiences of sound. Deleuze’s philosophy also highlights the idea of “becoming” and the transformative potential of sound. In this sense, Deleuzian sound studies is concerned with the ways in which sound can disrupt and transform established power structures.

By focusing on the materiality and affective dimensions of sound, non-representational theory enables a deeper understanding of how sound operates in different contexts and how it affects our bodies, emotions, and perceptions. Non-representational theory encourages an exploration of the forces, affects, and intensities on the bodies that arise from sonic phenomena, presenting sound not only as a tool for conveying meaning. It then allows for the exploration of the ways in which sound becomes intertwined with social, cultural, and political processes and how it contributes to the production of subjectivities and the shaping of our lived experiences.

The tensions between sound as a disciplinary-biopolitics practice and sound as an auditory disruption to everyday life are then crucial in this paper. Sound can be seen as a complex, multifaceted, and flexible matter and requires consideration of its force, affects and intensities, whereby the semiotics of certain slogans and the sonic materiality of the loudspeakers’ sound can produce subjectivity in human bodies and perception. By incorporating Deleuze’s non-linguistic principle, I expand upon my linguistic perspective on biopower. This consideration can aid in and be supported by the consideration of sound as a tool of biopower, beyond conscious thought and language.

SLOGANS AS AGENTS OF POWER

In the case of Covid-19, one can see the two forms of biopower: the disciplinary power and the biopolitical power. Lock-downs, mandatory vaccination, mask rules, and social distancing are reflections of power that produces “docile bodies” through discipline and administers populations by optimising them (Foucault, 1990). This leads me to the question of whether the act of broadcasting these slogans to ensure compliance can be looked at through the lens of biopower. I am going to argue that the use of sound from loudspeakers can disrupt habitual patterns of thought and behaviour in listeners by creating a sense of urgency and immediacy, fostering unity and solidarity among listeners. And instead of a transformation, these disruptions can potentially reinforce the established power structures, particularly in the context of biopower.

COVID-19 appears to be more of a symptom of waging a certain war to restore forgotten memories than a health emergency that would affect everybody physically. It is important to firstly consider the reasons for using war imagery in these slogans and the loudspeaker as a historical medium in the historical context of Vietnam. A large part of the Vietnamese cultural identity is built around national unity against “foreign invaders.” The country’s history textbooks focus heavily on heroic sacrifices and revolts against foreign rule, such as wars against France, China, and the United States. By framing the virus as an enemy (“invaders”) and encouraging citizens to view themselves as “soldiers” in the “fight” against it (“Fighting against the pandemic as fighting against invaders!; “Every citizen is a soldier in the fight against Covid”), the authorities used the war imagery as a cognitive tool for people to connect a recognisable concept of war “against invaders” to an unfamiliar one—the Covid-19. The coronavirus provided a unique case study in that there is an instant memory of public reminiscence that is embellished on par with war memory. Slogans such as “Victory through faith” and “Believe in Vietnam!” encourage citizens to have faith in the government’s ability to “defeat” the virus, as the country has not only once but three times defeated the invaders in history. This emphasis on faith and belief can be seen as a way of recalling the past memory, ensuring the public about a “victory” that can take place once again, and training the individuals’ perception to trust in the government’s authority and follow its directives. “Fighting the pandemic with iron discipline, behaving humane with all those who are isolated” manifests both the biopolitics and disciplining power, exerting control over the population by regulating their behaviour.

By tapping into collective memories, the Vietnamese government attempts to evoke associations of the past wars with the by-then situation, recalling the national collective memory of the wars ending with victories, aiming to gain higher trust in the state, and calling for solidarity and compliance. The members of the population were supposed to be encouraged by the government to value and practice “everyday heroism,” to be the “soldiers” fighting for the country’s “victory.” The language of war imagery is applied to a wide range of threats having nothing to do with military conflict, implicitly at least, which tend to validate the exercising of norms, of subjectivity, and of power. To the extent that war rhetoric shapes the public discourse, those questioning the emergency suppression of rights or the specific executive decisions of leaders can more easily be re-framed as “weak”, “unpatriotic” or lacking in solidarity. This is present in the slogan “To stay at home is to love your country,” which normalizes the act of staying at home as a declaration of patriotism.

In order to mediate their message about managing and controlling the population’s health, the authority also emphasises the importance of medical professionals in the fight against COVID-19 through loudspeakers on a daily basis. Slogans such as “Doctors and nurses are storm-troops in the frontier against the disease” immediately offer a picture of the whole nation as part of a camp on a battlefield. By exclusively referring to the war, the government recruits medical workers to be part of the national response to a time of uncertainty. The comparison between “doctors,” “nurses,” and “storm-troops” proceeds to legitimize the healthcare professionals’ work as a mission, a necessary sacrifice and responsibility to deal with the uncertain situation at the most dangerous and precarious position. It can also trigger a feeling of gratitude in the citizens, reminding them that everyone is in charge of different positions in this “war.” The prevailing narrative of uniting the people to justify the willingness of going to war is challenging, yet it is the collective memory that was touched upon that has worked as an efficient means to regulate individual behaviour, and produce obedient subjects and voluntary servitude. In fact, not only medical professionals, but many young Vietnamese have independently volunteered to help at COVID-19 posts, hospitals, and quarantine camps, expressing their resolve to “win” the pandemic.

One of the key features of biopower is its focus on the health and well-being of populations, which can be evident in the slogans presented above. According to Foucault, the logic of biopower is best understood as a logic primarily oriented to “ends,” that is, it sets out the population as its object and the well-being or prosperity of this object as the end toward which specific biopolitical measures are to be oriented. The increasing importance of biopower through the use of loudspeaker’s slogans can then be seen to take two mutually reinforcing forms: on the one hand, the prominence of disciplining techniques foregrounding war imagery as a means, and on the other hand, an increasingly biopolitical interpretation of the good of the population as an end to be addressed by these means, which includes both the good of being able to protect one’s health and the good of being a “heroic” citizen who takes part in the “fight against COVID-19” pandemic. In this sense, the well-being of a citizen is rendered not only as one’s health but also as a useful docile body in the national “fight” against COVID-19.

The patriotic act of “fight against Covid-19” that each citizen can do, however, is authorised by the mandate to “stay home” (“To stay at home is to love your country”). In a country that lacks infrastructure in its health system and cannot afford expensive mass testing equipment, it is in question whether this is a protection of the health system or protecting life itself. This discourse surrounding pandemic management suggests that lockdown measures and the slogans highlighting them are not only necessarily implemented to save lives but also to avoid overwhelming hospitals and public health services. And to be able to attain that, the use of war imagery is considered inevitable to display that the compliance of each citizen is equated to a patriotic action, rather than to unravel that the isolation of each household can help reduce the scarce resources spent on the patients to avoid the collapse of the health system and to stop the spread of COVID-19 while there was no vaccine at the time. Framing a novel obstacle by tapping into collective memories, common identity, and history can reinforce the citizens’ heightened gravitas, calling for their sacrifice of freedom for a period of time, ensuring that their compliance is equated to their high trust in the state and that their well-being as “heroic” citizens will be compensated. The slogans broadcasted to ensure the lockdown measures also revealed a homogenizing policy that does not take into account inequalities and different types of vulnerability. It introduces a policy of imposing discipline and micromanagement of bodies, assuming the existence of a population with equal opportunities, life chances and access to resources.

By rendering the war imagery in the slogans, the government has legitimized the warlike strategies with the complacency of the whole population, normalizing the rhetoric resource of the pandemic danger and justifying the acts of disciplining imperative for making (rather than letting) live. If biopower is structured by the alternative between “making live” (biopolitics) and “fighting for life” (discipline), the Vietnamese government’s responses to the COVID-19 virus have been justified publicly by a biologisation of the population. These slogans then suggest something distinct from the transparent information conveyed in the rest of the broadcasting content. The inherent tension lies in the government’s utilisation of the uncertainty to solidify its authority while simultaneously attempting to address historical grievances. The fact that the slogans were used to exploit the COVID-19 situation as a means to address and potentially alleviate historical trauma inflicted by the communist regime highlights the complex dynamics at play, raising questions about the extent to which genuine political reformation can be achieved. It risks perpetuating and reinforcing the existing power structures, suggesting a short-lived moment of transparency and hope may ultimately yield little in terms of long-lasting transformation, limiting the potential for significant societal changes.

SOUND AS A MATERIAL & AFFECTIVE PROCESS

If we consider noises as a constant flow of the social and cultural dynamics of the urban space, according to Deleuze, the being-out-of-place of the silence refers to the occurrence of certain amounts of disruption, instability, disharmony, and the undermining of dominant productive activities.

While noise rises as an index of movements and physical presence, a register of daily behaviour, silence and silencing may form an index of the limits of specific social environments. An auditory sound space that exists within the meeting between noise and silence in this particular context of the pandemic can create an acoustic articulation that signifies what is permissible. Deleuze defines force as the capacity to affect or be affected, which is constantly in motion, creating new forms and effects. In this context, noise, silence, and its ultimate shift, although they appeared as a result of a physical measure to ensure the restrictions and lockdown, have created a force that indeliberately impacts the acoustic environment around the interviewees. In this regard, silence circulates as a projected constraint in the sound environment, supplying the signifying gesture of silencing with ideological weight and finding deeper expression in forms of physical restriction. It can then function as a partial form of control and isolation in order to confine the human body within its restrained, permissible space.

The silence resulting from the lockdown has heightened the interviewees’ awareness of the surrounding sounds, particularly as the sudden silence of urban spaces became more noticeable. Intensity, in Deleuze’s philosophy, refers to the degree or level of force present in a given situation. The pandemic and resulting lockdown measures have created an intense situation that has altered the intensity, vibrancy, and volumes of different sounds in the urban soundscape. The sudden reduction in noise levels has increased their sensitivity to the remaining sounds, such as birds, neighborhood sounds, and the echo of loudspeakers. The very first affect that this soundscape movement can register in the interviewees is a heightened sense of intensity and awareness of the sounds around them. If they started to live in a much more “silent soundscape” (Schafer, 1969) that produced ecological effects on their environment, it must also be recognized that this apparent “peace” has not always produced necessarily positive impacts on the individuals’ psyche, especially when there was an audible medium (the loudspeakers) above the interviewees proclaiming a virus of high lethality lurking around them.

Regarding loudspeakers, sound can effectively create a sense of presence because it does not abide by boundaries that distinguish between public and private life and can extend beyond the limits of what is visible. Even when the source of sound cannot be perceived by the human eye, it can still be imagined and experienced in the auditory realm. Sound thus can be comprehended not solely as a physical manifestation of acoustic properties but also as the semiotic presence of the voice, encompassing vocal expressions, conceptual and physical silence, noise, subjective experiences of both internal and external auditory perception, and the focal point of attentive listening (Cluett, 2013). In this context, the sounds emanating from the loudspeakers not only carry the sonic materiality but also symbolise the authority’s voice, serving as a means of its expression and control. They embody the audible presence of the government broadcasting its directives and slogans, the interplay between silence and noise, and serve as subjects of both internal contemplation and external perception.

By projecting the voice from above, the loudspeaker is authorized a position of subjective force, commanding attention and conveying a sense of dominance. The physical positioning of the loudspeaker serves as a symbolic representation of authority, amplifying the messages it carries. This symbolic significance invokes a perception of transcendence, where the voice of authority is perceived as emanating from a higher realm and possessing a heightened level of legitimacy and control. The loudspeakers were thus a powerful force that contributed to the production of subjectivity, shaping the way the interviewees perceived and interacted with their surroundings. Here it is possible to get an idea of what the medium’s name is: public address system. In this way, the interviewees’ observations highlight the intricate relationship between the authority and the public, the sound’s positioning, and its origin. The potency of the loudspeaker to act in the service of government measures during the pandemic was readily evident. The effectiveness of its operation for the public, however, is a separate matter that can be further explored in subsequent discussions.

The amplification of sound relied on physical structures and human exertion to increase its volume or amplitude. However, with the introduction of the loudspeaker, a new dimension of authority and power emerged. The loudspeaker, with its loudness as a crucial factor in shaping subjectivity, allows authority figures to address a large audience from a distance, maintaining a sense of distance and unapproachability. Its sheer volume and projection enable domination and control over the sonic space. During the lockdown, amidst the interplay of silence and suppression intertwining in an unsteady weave, the sounds emanating from loudspeakers become more pronounced and distinct than ever. They cut through the prevailing quietness and the constraint effects of the forceful grip of the arresting volume, leaving a forceful impact. The authority’s voice, amplified by the loudspeaker, retains its power irrespective of whether individuals actively recall it or are unable to escape its overwhelming volume. For Deleuze, the consciousness that the listeners have in this case can be “inseparable from a triple illusion that constitutes it: the illusion of finality, the illusion of freedom, and the theological illusion’ (1988, 20).

REFERENCE LIST

Cluett, S. A. (2013). Loudspeaker: Towards a Component Theory of Media Sound. Princeton University.

Deleuze, G. (1995). Negotiations, 1972-1990. New York: Columbia University Press.

Deleuze, G., and Guattari, F (1988). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. London: Athrone Press.

Foucault, M. (1926-1984). Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the Collège De France, 1975-76. New York: Picador.

Foucault, M. (1976). The History of Sexuality. New York: Pantheon Books.

Foucault, M. (1982). ‘The subject And Power’. Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism And Hermeneutics. 208–226. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

Ha, S. T. 2020. “Chống dịch như chống giặc [Fighting the disease as invaders].” Bao Dien tu Dang Cong san Viet Nam, April 2, 2020. http://dangcongsan.vn/tieu-diem/chong-dich-nhu-chong-giac-551842.html

Long, V., and Hai, D. (2021). Digital Nationalism during the COVID-19 Outbreak in Vietnam: Collective Forgetting and Domestic Xenophobia. Southeast Asian Media Studies Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1.

Nguyen-Thu, G. (2020). ‘From wartime loudspeakers to digital networks: communist persuasion and pandemic politics in Vietnam’. Media International Australia. 177(1), 144-148. Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1329878X20953226

Võ, H (2017). ‘War-time loudspeakers to continue blaring out across Hanoi despite huge public opposition’. VnExpress, 2 April. Available at: https://e.vnexpress.net/news/news/war-time-loudspeakers-to-continue-blaring-out-across-hanoi-despite-huge-public-opposition-3564352.html (accessed 14 May 2022).

Schafer, M. (1977). The Soundscape. Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books.