THE COMMODIFICATION OF THE SOUL: TECHNOLOGY, CONTROL, AND THE FUTURE OF HUMAN EMOTIONS

The battle for the mind will be fought in the video arena, the videodrome. The television screen is the retina of the mind’s eye. Therefore, the television screen is part of the physical structure of the brain. Therefore, whatever appears on the television screen emerges as new experience for those that watch it. Therefore, television is reality, and reality is less than television. Professor Brian O’Blivion in Videodrome

In an era where digital technologies have permeated nearly every facet of daily life, the boundaries between human experience and technological intervention are becoming increasingly indistinct. The fusion of media, capitalism, and digital expansion has led to profound shifts in how we perceive reality, express emotions, and interact with each other. But they can always go further. Let us imagine, for instance, a dystopian version of streaming platforms where every show you watch is not just personalized based on your interests but crafted in real-time based on your emotional responses. In such a techno-social arrangement, emotions are transformed into data, becoming commodities within an all-encompassing digital economy.

This text speculates on the implications of such a dystopia, where emotions, once considered deeply personal, are reconfigured as transactional elements within a technologically dominated society. By examining David Cronenberg’s cinematic portrayals of techno-human entanglements and the interactive narrative of the video game Cyberpunk 2077, the text seeks to speculate on how contemporary digital platforms and devices — far from being mere tools — shape human perceptions, values, and a sense of the self.

Cronenberg’s dystopian visions: Technology and humanity in Videodrome and beyond

David Cronenberg’s films, particularly Videodrome and eXistenZ, extend beyond conventional horror to probe deep social and cultural anxieties, diving deeper into the interaction between humans and technology. Known as a master of body horror — a genre that may not appeal to everyone — Cronenberg’s work resonates with the thoughts and concepts of key 20th-century media theorists. Cronenberg’s films can be read as allegories of technosociety and culture, where the mutations of science, technology, capital, and humanity give birth to new species, realities, and forms of social and cultural organization (Kellner, 2019).

Reflecting on the epigraph above, it is worth considering what Videodrome (1983) is really about. The main character, Max Renn, runs a small cable television station and discovers a signal for a mysterious show called Videodrome, which features scenes of violence and torture. As Max delves deeper into this world, the show begins to have a destructive impact not only on his mind but also on his body, leading to physical mutations and hallucinations. Max can no longer distinguish what is real from what is a product of media culture.

One of the key ideas of the film is that modern media can control consciousness and perception of reality (Porton, 1999). The television is portrayed as an organ of vision that penetrates the individual, altering their perception and making television more than just a tool. Professor O’Blivion’s phrase in the film, “The television screen is the retina of the mind’s eye”, underscores this notion — television captures reality, and reality becomes less significant than media.

While Cronenberg sometimes presents himself as a Cartesian dualist in interviews (e.g., Cronenberg, 1981), his films deconstruct the opposition between mind and body. In Videodrome, media are shown not merely as channels of information, but as viruses infecting consciousness and altering bodies. The virus metaphor is key here — Videodrome induces physical mutations and hallucinations, turning people into a new post-human species, merging technology and flesh. This virus invades the body, breaking down the boundaries between what is real and what is illusion.

In Cronenberg’s films, the mind is subject to control by both psychic and material forces, while the body is vulnerable to assault by cultural and technological forces, leading to horrific mutations. Cronenberg concretizes McLuhan’s vision of media as the exteriorization of the mind and body, which then collapse into the human, creating new configurations of experience and culture:

Although there is a technophobic element in his depictions of technologies and experiments, for Cronenberg, the cataclysms of our era are the product of the conflation of nature, science, technology, the media, capital, and humanity, and thus cannot be blamed on any single factor (Kellner, 2019, p. 270).

In the later film eXistenZ (1999), Cronenberg delves into more modern technological themes, such as virtual reality and biotechnology. The protagonists, video game designer Allegra Geller and her bodyguard Ted Pikul, find themselves inside a game called eXistenZ, which connects to the nervous system through an organic interface. Virtual reality connects to the body via biological ports, and the game controller is not a plastic joystick, but something like an organic creature with an umbilical cord. Technologies become an inseparable part of the human, physically merging with them — they begin to change and transform the human body. As they play, the boundaries between the real world and virtuality become increasingly blurred. The audience is left to wonder: what is reality, and can virtual reality be just as genuine as physical reality — not only for the film’s protagonists but for all of humanity?

Cronenberg is not anti-technology and attempts to portray the new technoscape as both one of the great cataclysms of modernity and a potentially higher, better stage of history (Arnold, 2016). His position allows for developing a critical view of the influence that capitalist technologies from leading IT companies have on modern society. However, Cronenberg’s films are, after all, fantasies and reflections — more importantly, they were released in the 20th century, while the 21st century has brought some of Cronenberg’s more speculative ideas into reality.

Cybernetic futures: How Cyberpunk 2077 envisions a world governed by tech giants

Challenging audiences to reflect on the evolving relationship between human experiences and technological advancements, Cyberpunk 2077 not only captivated the imagination of gamers worldwide but also sparked discussions among academics, researchers, and industry professionals about the plausibility and consequences of a technologically dominated future. Set in a dystopian landscape, Cyberpunk 2077 presents a detailed vision of an urban society governed by powerful corporations that dictate the trajectory of technological advancements. These IT giants have embedded new cybernetic devices — specifically, Brain-Computer Interfaces — deep within society, transforming it into a complex network of emotional, psychic, and digital connections. This device, initially celebrated as a technological breakthrough, now governs the very fabric of human experience, intertwining emotions, memories, and even dreams with the digital realm. It is no longer about simply tracking human behavior or predicting preferences — it is about manipulating the deepest layers of the human soul in real time. In this speculative future, the Brain-Computer Interfaces functions as the ultimate capitalist tool. They are not just a gadget — they are a tool of power. Owned by the corporate megastructures that dominate all media and data flows, the device allows corporations to harvest not just emotions but souls.

Although these are merely reflections on the future, technologies that intertwine our emotions with the latest scientific advancements are already a reality. Systems like Amazon Alexa and Google Assistant are advancing to recognize the tone and emotional nuances in the users’ speech (Google AI Blog, 2020; Amazon Developer Blog, 2019). Companies are working to make these devices capable of adapting their responses to match a person’s mood, creating a more “personal” and emotionally aware interaction. For example, virtual assistants can adjust their responses to reflect the emotional state of the user, offering comfort or encouragement, thus fostering a sense of emotional closeness or connection. This concept aligns with the broader goals of making artificial intelligence more “human-like” in its interactions, facilitating a stronger emotional connection with users. However, under the guise of improving user experience, these complex capitalist mechanisms are at play, aimed at binding users to platforms, fostering a sense of complete comfort, and even cultivating dependency. The more users post and interact with content, products, or services, the more information IT corporations collect about them — this is data that holds significant monetary value, as it is sold to advertising companies for targeted marketing purposes.

In certain techno-pessimistic approaches, however, scholars focus not so much on the monetary value of this data, but on the methods by which it is extracted. In turn, the idea of “surveillance capitalism” (Zuboff, 2019) illustrates how data can be used for the control and manipulation of individuals. Specifically, it is used so to predict their current and future choices, leading to the creation of what is known as “behavioral futures markets”. Shoshana Zuboff notes that capitalism has progressed beyond monitoring users to directly influencing them, intervening in human action to manipulate, tune, herd, and modify behavior towards predetermined outcomes. Surveillance capitalism, where corporations employ surveillance and control technologies to manage the behavior of citizens and businesses, is the result of a malignant mutation of capitalism; and the most complex aspect of this tendency is that users have entered into a Faustian bargain. They agree to constant monitoring of their entire existence to gain access to digital technologies and services, unaware that they are making a fundamentally illegitimate choice.

“I’ll lend you my aid and give you delight, if later you give yourself to me outright” (Faust, Goethe)

Emotion as commodity: How technology governs emotion and behavior

Data is not limited to our clicks, likes, navigation, or time spent on a platform. Data also encompasses our emotions: affection, obsessions, aggression, depression, shock and delight, fear and disgust. They are harvested, repackaged, and sold to advertisers, governments, and content creators. As it may sound like Black Mirror episode, reality shows the true picture: Facebook’s internal documents revealed that the company could already infer users’ emotional states to target ads more effectively (e.g., targeting teens during moments of vulnerability). These personalized narratives generate profit not just from viewership, but from the sale of your emotional data to advertisers and governments seeking to control populations on a molecular level. Franco Berardi, in his book The Soul at Work (2009), calls this phenomenon “semiocapitalism”, where the ability to generate ideas, create compelling content, or evoke emotions becomes a product that can be bought and sold. Individuals become intertwined with the capitalist system, constantly producing value even outside traditional work hours — whether by sharing personal stories on social media or brainstorming ideas for the creative industries.

Let’s speculate further: imagine a scenario where real-time emotional feedback is no longer just a way for companies to personalize content. Instead, entire media ecosystems operate on emotional economies — the more powerful your emotional responses, the more value you generate. This creates a hierarchy of consumers, where those with the most intense, passionate reactions are rewarded with exclusive content, bonuses, and status within digital networks. The feedback loops between emotions and content become so precise that the services and products begins manipulating the emotional states of individuals to maximize engagement. These platforms adjust their content dynamically to evoke the most intense responses — whether joy, fear, anger, or sadness — to keep users engaged. But while the society is required to constantly engage their emotional and mental capacities, it forces individuals to perform feelings they may not genuinely experience, further disconnecting them from their true selves. Individuals are no longer passive consumers of content; they are generators of real-time emotional data, which is instantly fed back into the media networks. This aligns with Jenkins’ (2006) concept of participatory culture, but here participation means full exploitation. Instead of empowering users, it commodifies their emotional states.

Adding to this line of critique, Han (2017) argues that digital technologies do not impose power through overt coercion but rather facilitate new forms of control by fostering voluntary participation and self-regulation. In the digital age, individuals willingly submit to systems of constant monitoring, believing this enhances their connectivity, productivity, or self-expression. Social media platforms, for instance, offer a seductive promise of empowerment — through likes, shares, and visibility — while subtly conditioning users to conform to algorithmic demands. Power no longer needs to act externally; it is internalized as users self-monitor and self-optimize, ensuring their behavior aligns with the imperatives of the digital system. This resonates with Foucault’s (1977) theory of biopower, which conceptualizes power as a mechanism that governs life by regulating bodies, behaviors, and populations. In the digital sphere, this biopolitical control operates not just through institutions but through pervasive surveillance and algorithmic manipulation. The commodification of emotional and cognitive labor turns individuals into resources for a ruling elite of platform owners, advertisers, and governments. This creates a system where power is exerted at the molecular level, embedding itself within the intimate fabric of daily life.

The political implications of this are profound. By harvesting and monetizing emotional data, platforms reinforce existing hierarchies and centralize control in the hands of a few corporations. Emotional manipulation becomes a tool for maintaining dominance, shaping not just individual behavior but societal norms and political realities. For example, platforms can amplify outrage to deepen polarization, influencing elections and public opinion to serve their economic or ideological interests. This form of biopolitical governance ensures that every interaction — whether conscious or subconscious — feeds the machinery of surveillance capitalism.

Drawing on Althusser’s (1971) concept of ideological state apparatuses, services, products and platforms operate as a powerful ideological tool, manipulating individuals not only at the level of ideology but directly through their emotions and thoughts. This is more than the simple media influence — it is a direct modification of human perception and reality, which turns Baudrillard’s (1994) hyperreal into an ideological apparatus in the Althusserian sense. In other words, this futuristic capitalist governance is not beyond ideology but is the ideology par excellence, as the boundaries between reality and representation dissolve, leaving humanity trapped in a simulated experience controlled by corporate powers. Control over IT services means control over human experience itself. Corporate giants effectively own the inner lives of millions, using their deepest emotions as fuel to generate profit and influence.

The inescapable digital matrix: Can we reclaim control over our emotional data?

In connection with this, the question arises: can there be any escape from a world where emotions are not just shared but manufactured and sold? In a hyperconnected world, complete withdrawal from systems of emotional commodification might be utopian. Instead, true freedom in this context might not mean escaping entirely but rather reclaiming agency over how emotions are experienced, expressed, and shared. For instance, Zuboff (2019) concluded that the only way out of this situation is to take control of one’s own data.

The reality, however, is that this is unlikely to be possible. There are known cases globally where users have accused social networks of excessive data processing and demanded that the platforms hand over the data they have stored about them (Fuchs, 2014). Although they had deleted their accounts, they received a printout of more than 1200 pages of personal data that the platform had been storing about them.

In some cases, this dependency arises not only from corporate strategies but also from the passivity of the users themselves. Couldry and Mejias (2019), who wrote on “data colonialism”, compared the current trend of exploiting user data to the colonialism of the New World. At that time, the Spanish read the Requerimiento — a document that effectively declared the land to be the property of Spain — to the inhabitants of villages and towns in the New World. They read it in Spanish, so none of the inhabitants understood a word. Mejias notes that there are many similarities between this historical event and today’s terms of service and agreements: users pretend to read them, but they are written in a language they do not understand. This is supported by public research: as researchers from the American agency Deloitte found (Businessinsider.com, 2017), 90% of users never read user agreements. Among the younger generation, this statistic is even worse: 97% of 18-24 year olds. Respondents said that the language of legal documents is so complex and difficult to understand that they do not bother to familiarise themselves with the text. They are willing to give away their data without a second thought in exchange for comfort. This, in turn, allows corporations to greatly expand their methods of manipulating users.

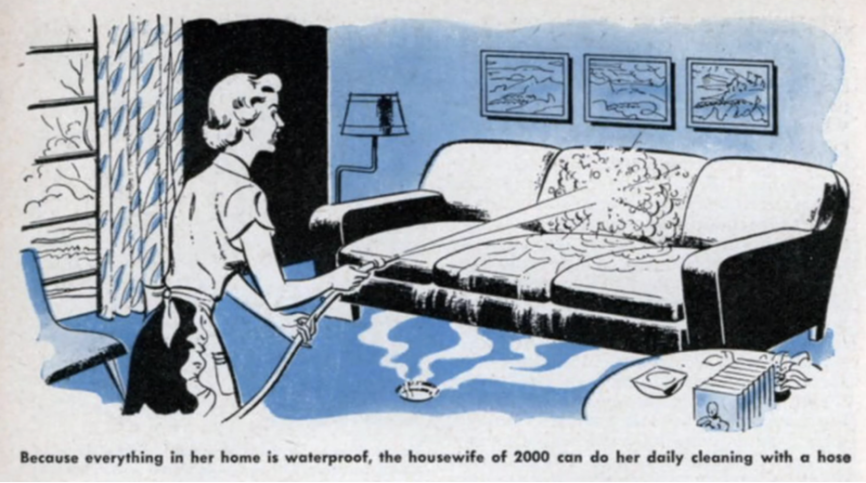

Of course, many scholars may criticize the act of speculating about the future, arguing that it is nearly impossible to predict accurately. A frequently cited example is an imagined vision of the year 2000 by Waldemar Kaempffert, published in Popular Mechanics in 1950:

When Jane Dobson cleans house she simply turns the hose on everything. Why not? Furniture (upholstery included), rugs, draperies, unscratchable floors – all are made of synthetic fabric or waterproof plastic.

In the mid-20th century, people envisioned a future dominated by plastic and synthetic materials, reflecting the materials’ novelty at the time. Yet, as we can see, this vision did not align with our current reality. Similarly, when we speculate about the world of 2077, can we really foresee a future where biotechnological devices infiltrate our minds, shaping our dreams and emotions? Is this merely a distant fantasy — or could it already be becoming a reality?

In the end, the line between speculative fiction and reality grows thinner by the day. As technology advances, we are left to wonder if Cronenberg’s terrifying visions are still confined to the screen or if they are gradually materializing around us. Just as Videodrome’s protagonist, Max Renn, becomes consumed and transformed by a media signal that merges with his body and mind, our own society inches closer to a world where technology does not merely serve us, but becomes a part of us — muddling the self and the machine. What seemed like far-off science fiction, might, in fact, be the foundation of our present — and possibly future. The question remains: are we heading towards a future of unprecedented integration with technology, or is this just another imaginative vision destined to remain fiction?

X.

REFERENCE LIST

Althusser, L. (1971). Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays. Monthly Review Press.

Andrejevic, M. (2011). Reality TV and the Work of Being Watched. Rowman & Littlefield.

Arnold, N. (2016, October 23). 7 of horror director David Cronenberg’s most twisted movies. Cheatsheet. https://www.cheatsheet.com/entertainment/7-mind-bending-cronenberg-films-every-fan-should-see.html/

Baudrillard, J. (1994). Simulacra and Simulation. University of Michigan Press.

Berardi, F. (2009). The soul at work: From alienation to autonomy. Semiotext(e).

Couldry, N. & Mejias, U. A. (2019) The costs of connection: How data is colonizing human life and appropriating it for capitalism. Stanford University Press.

Cronenberg, D. (1981). Article and interview by Paul M. Sammon. Cinefantastique, 10(4), 6.

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Pantheon Books.

Fuchs, C. (2011). Foundations of critical media and information studies. New York: Routledge.

Haraway, D. (1985). A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century.

Han, B. C. (2017). Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and new technologies of power (E. Butler, Trans.). Verso.

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. University of California Press.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York University Press.

Kellner, D. (2019). Media Culture: Cultural Studies, Identity, and Politics in the Contemporary Moment (2nd ed., 25th Anniversary ed.). Routledge.

Marx, K. (1867). Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (Vol. 1). Penguin Classics.

Porton, R. (1999). The film director as philosopher: An interview with David Cronenberg. Cineaste, 24(4), 6.

Smythe, D. W. (1977). Communications: Blindspot of Western Marxism. Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory, 1(3), 1-27.

Van Dijck, J. (2013). The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. Oxford University Press.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. PublicAffairs.

Amazon Developer Blog. (2019). Advancements in Emotion Recognition with Alexa. https://developer.amazon.com/blogs

Businessinsider.com. (2017, November 15). You’re not alone, no one reads terms of service agreements. https://www.businessinsider.com/deloitte-study-91-percent-agree-terms-of-service-without-reading-2017-11?r=US&IR=T

Google AI Blog. (2020). Toward Emotion Recognition in Voice Assistants. https://ai.googleblog.com