VIOLENCE AND THE LANGUAGE OF MODERN MEDIA

In 1998, a reality show titled Susunu! Denpa Shōnen aired in Japan. The show operated by broadcasting real-time footage of contestants partaking in extreme challenges, exposing them to the perils of physical or psychological harm. One of the most controversial but most successful series of regular broadcasts of the show was Nasubi Show, featuring Susunu! Denpa Shōnen’s most famous contestant, Tomoaki Hamatsu under his stage name Nasubi (translated to English as ‘Eggplant’). Nasubi was stripped of all his belongings, including his clothes, and placed in a small room containing only a table and a shelf filled with commercial magazines. The challenge for him consisted of staying in the room without any contact with the outer world for as long as it would take him to amass 1,000,000 yen (roughly 10,000 USD) in mail-in sweepstakes winnings. His room was equipped with a camera, which livestreamed his actions, with highlights rebroadcast every week. The catch is that Nasubi was not aware of the livestream, as he was told the recording would be reviewed and broadcast after he had completed the challenge. It took Nasubi 335 days and tens of thousands of contest entries to total a million yen in winnings. The latter varied from bags of rice to a PlayStation, a bicycle, or a 10,000 yen voucher. Keeping in mind that Nasubi was not provided any allowance or support on behalf of the producers, his only survival resources were sweepstakes winnings, leading him to starve for days on end and eat raw rice or dog food when nothing edible was available. He never won any clothes, despite specifically targeting sweepstakes for articles of clothing at the beginning of his ordeal.

By the time the challenge was complete, Nasubi had gained 17 million regular Japanese viewers, so the producers decided not to end it just yet. Nasubi was blindfolded and relocated to Korea, where his new challenge was announced: he now would have to win enough to pay for an economy-class airplane ticket to Japan. Still, the required sum only grew, and Nasubi was not returned to Japan until he had amassed enough to pay for a first-class ticket. The whole show lasted for 15 months and ended in a grand finale of Nasubi being led into another “room” blindfolded, only for the walls of the room to collapse, exposing him, naked, to a live audience of hundreds of people cheering for his victory. The show left Nasubi struggling to wear clothes or keep the conversation going.

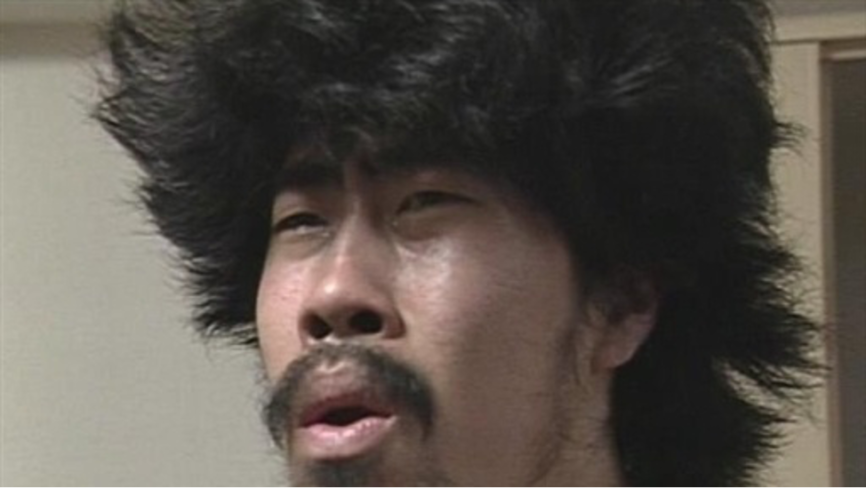

Figure 1. Still from the Nasubi show

A CRUEL EXPERIMENT

Now, whether the show was a cruel experiment or not is not the question to ask; the real issue is how Nasubi’s suffering of starvation or mental breakdowns was broadcast to an unprecedentedly large audience and what could be the appeal of this sort of entertainment[1].

As mentioned above, regular highlights would be posted of Nasubi’s most memorable moments of the week, including crying out of hunger or desperation. Notably, the highlights would feature this concerning footage with light-hearted subtitles, sound effects, or animation, such as little hearts and laughter, added on top of the original sound of Nasubi breaking down. These additional effects were the main functional element of the show, forging Nasubi’s suffering as media content. In the same way backstage laughter accompanies comedy shows, sound effects were applied to Nasubi’s real-life footage to signify it as an object of media consumption mindfully orchestrated for the audience to enjoy. What would otherwise be enticing empathy appears laughable framed as a highlighted moment of a reality show: Nasubi was bereft of a right to compassion as his life had been mediated, commodified as property of the producers marketed towards the audience.

This show fiercely challenges the binary of privacy and publicity through its operational differences from reality-shows most known to Western viewers, such as ‘Keeping Up with the Kardashians’ or ‘Survivor’, where a lack of real-life broadcasting and the expectation of a script being implemented reserve some privacy for their participants. The audience fully understands that most scenes of the show are not as spontaneous as they claim to be but demands they be played as if they are exclusively guided by the instantaneous emotions and intuition of the actors. In other words, a generic reality show is a make-believe play, where actors act out ingenuity and viewers perform cluelessness. In fact, some studies show that reality-show viewers are interested in the curiosity of interactions; they tend to picture themselves in the same conditions and wonder how they would have acted (Perales Bazo, 2011). An inference arises that what makes the show prepossessing is not even their aspiration to mimic reality but to invert it instead to “spice up” the domestic routine. Someone else’s life is worth watching if it is interesting—more dramatic, more romantic, more dangerous – and reality shows allow their audiences to live out that life through the actors. There is a transposition of desire in place, which renders reality-shows purely Symbolic in a Lacanian sense: the desire confined to the Imaginary is unattainable and its symbolic representation in the shows eschews its frustration to the realm of the Real but provides limited access to its enjoyment via mediating it. Mediation does not set the viewer as the primary subject of enjoyment, on the contrary – it solidifies the boundary of the Imaginary and the Real – but provides a glimpse of this enjoyment, satisfaction of desire, which could, frankly, cease to be enjoyable once frustrated with the order of the Real (Žižek, 1998). To put it more directly, violence, cruelty, or dramatic romance are enjoyable while experienced indirectly but painful and unpreferable once perceived by one’s own senses. The cruelty Nasubi was subjected to tears the boundary apart, as what is being broadcast in real-time is his genuine experience, all the pain and suffering he has gone through as well as the ostensible harm it has done to him. A camera turned on at all times and transmitting its footage to millions of users transcends even the breach of privacy enjoyed by followers of live-stream bloggers. No matter how long the stream, the blogger fully retains the choice to put an end to it, while Nasubi was not even aware of the footage being aired. The Nasubi show is, therefore, a play of experienced privacy made public, granting the audience a unique viewing experience. However, we might ask whether ‘violence’ is an applicable term to describe his ordeal: would it be enough to condemn the subjective violence exerted by the producers?

THE VIOLENCE OF NASHUBI

I state the answer to the latter inquiry as negative. The violence Nasubi faced was not derived from the ill intent of the production company but rather from the hecceity of the media reality he subjugated his life to. It is an objective reproducing quality of the system that deprived Nasubi of sociality, reducing him to a primal state of ‘hunting’ for food and fighting for survival with a pen and a bunch of mail-in sweepstakes. The mechanism of assigning legitimacy to objectively cruel deeds is powered by the authority of television. The sovereignty of the audience carries out divine violence upon the contestants of Susunu! Denpa Shōnen: violence has been exerted but no victim is in place and no crime has been committed (Žižek, 2008) for all the contestants were willing to participate, fueled by their strive towards fame and wealth.

It must be added that Susunu! Denpa Shōnen is not the only reality-show on Japanese television that is defined by violence; it is a common theme for shows to picture their participants in extreme conditions. A common hypothesis regarding how this came to be is that the audience of salarymen with highly routinized daily experiences is hungry for raw emotion, be it positive or negative, and extreme reality-shows bring exactly that. This line of thinking is congruent with my previous argument of transposition of desire as a factor in play for this media phenomenon, but the topic is not yet exhausted.

As a commodity, media phenomena are products of labor. Webcam-bloggers are working, in a sense, with their lives commodified to be produced rather than lived (Andrejevic, 2004); this life is no longer a subjective, authentic experience but a job, a monetized activity that has to meet a certain standard to remain profitable. On the other hand, media production relies upon reticent work, e.g., the endurance of Susunu! Denpa Shōnen is not directly paid with a promise of future earnings being the premise of participation. Furthermore, this work is not regarded as labor due to the media formatting it as willing participation, placing the contestants on equal footing with the viewers as enjoying subjects of the play. Such actors, including Nasubi, form, by analogy, the proletariat of mediated capitalism – bereft of legal protection and alienated from their labor. Supplementation of the previous argument with these labor dynamics affords to relate it to Žižek’s reasoning in ‘The Sublime Object of Ideology’ (Žižek, 2019), whereas a commodity is formed by labor, but its true value is endowed to it in a dream-form. Dream is the latent meaning of a commodity, the one that establishes its role as a symbol, a signifier for the realm of the Imaginary – the aforementioned desire shared by the audience. The content and sublime object of ideology in place for the media industry is enjoyment in the form of laughter, tears, or an orgasm, as in the next example we will refer to. To recapitulate, the work performed by Nasubi and other reality-show actors is dream-work or outplaying the dream as a production of satisfaction or desire.

An adjacent illustration to the main example of this paper is the result of an empirical study of the content shown to first-time users of popular porn sites that revealed 1 in 8 video titles to be describing an act of sexual violence (Vera-Gray, F., McGlynn, C., Kureshi, I., & Butterby, K., 2021) . Other studies estimate that between 35 and 88 percent of pornographic materials contain scenes of sexual violence or aggression (Fritz, Malic, Paul, & Zhou, 2020; Bridges, Wosnitzer, Schaffer, Sun, & Liberman, 2010). This example is employed to show that the tendencies described above are not specific to Japanese television but are ubiquitously present across platforms, genres, and languages. However, pornographic material might better illustrate the language of violence employed in Japanese reality-shows.

Women (who are usually the targets of aggression or sexual violence, as stated by the studies above) are depicted as sharing in the enjoyment of sexual violence. Despite including acts of extreme degradation and physical harm, the event being filmed in mainstream porn is not labeled as rape but rough sex, implying that both parties are consenting to whatever is happening and enjoying the process. In precisely the same manner, Nasubi is expected to share in the popular excitement regarding his hardship and Nasubi himself perfectly understands this expectation as normative: for fear of appearing ungrateful, he proceeds to perform his dance of victory every time he wins a sweepstake. Another noteworthy observation in line could be online sex-workers, performing enjoyment for their clients as a main form of labor.

All of the aforementioned postulated subjects of enjoyment are byproducts of the “society of control”—they aare socialized to be striving towards monetization (herein, monetization of desire). In this respect, we can also highlight the impact of control-socialization on the modus of our bodies being given to us. The body is given to a child as the body, which aligns vastly with their idea of selfhood, while social marking of that body renders it a body—a repository of assigned desire, which can be later retranslated into monetization. Therefore, a subject encased in the said body remains modulated by structural and corporate forces. A subject of sociality of control is forged with desire purposely inscribed as if it were a lacuna of freedom, a transgression of societal expectations, while this same transgression is fully subjugated to economic maximization. Desire, thus, becomes most aligned with the material and its consumption.

Some of the modes of consumption can address this lacuna to trigger an emotional response, such as disgust, whereas the access to desire thus gained simultaneously produces pleasure. The same mechanism is scrupulously described in Kim (2021) via an analysis of mukbang (eating shows). According to Kim, mukbang content habitually contains sounds, visuals, and acts that would be considered outright vulgar in a social setting, while also being revolting and exciting to its viewers at the same time.

What I want to state is that the observed cultural extremities denounced by many as perversions or torture are presupposed by the daily exclusion of desire for a post-modern subject. The catch would be that the common denominator in Nasubi shows and mainstream porn—mediation—is serving as the legitimation mechanism, rendering sexual violence an acceptable sexual practice and isolation and starvation a fun challenge. Mediation allows us to reimplement the said vulgarities into the social norm, interpret them with the language of normality and socialize them, just like that.

An eggplant would follow Nasubi around the room to cover his private parts, making the show light-hearted and dissolving the eerie atmosphere of an empty room inhabited by a haggard man. Moreover, joking subtitles and audio-effects would appear regularly, even during Nasubi’s darkest moments, to ensure the audience that there was no reason to worry—the show goes on and everything remains according to its plan. The same function is fulfilled by camera and editing work in porn: outstandingly disturbing scenes are cut out and the videoframes are put into such an order so as to narrate a story of mutual enjoyment.

The word ‘narrate’ takes the pivotal place in the previous sentence as the mediation of reality performs its alteration by turning an event into a narrative. In this sense, no media representation can be understood as objective or realistic, for the very act of narration assembles a story out of a plethora of disordered events. Every narration/story is told from a defined perspective, and this perspective alone defines the main characters, the plot, and the assignment of moral value to it. Through the choice of perspective, ideology is endorsed: choosing the “male gaze” in pornography leaves out the experience of the female actor outside the scope of her appeal to the male actor and viewer; choosing the perspective of a media producer means devaluating Nasubi’s suffering. As a result, the ‘genuine’ or ‘true’ reality loses its appeal and even its ontological value, with a story or a narrative taking its place as a comprehensible and enjoyable representation of realities.

Figure 2. Still from the Nasubi show

To put an end to this rumination, I would like to summarize my point as follows: Extreme visuals and concepts for media production are a functional derivative of media communication as such. Violence and disgust are a tingling sensation to a post-modern ego encircled by power structures: they allow for recognition of desire but simultaneously reintroduce it back to the social to avoid a genuine transgression in an act of tautological self-reference (Luhman, 1991). Communication is, effectively, acknowledgement and inclusion for the need for media to perform the communication.

Thus, no active transgression can be mediated while retaining those transgressive qualities. Collective transposed enjoyment arises out of it, already organized and monetized. As soon as the Nasubi show airs, fun emerges from starvation. Once something is placed in a museum, it is art; once something airs on TV, it is a show. The cultural system is capable of endorsing multiple alleged transgressions, depriving them of these qualities as soon as it finds a way to conceptualize it. All in all, no violence is unprecedented or unacceptable via public media, and the tautological reference of mediation will render everything even more natural, anticipated, and profitable.

x

[1] Atrocity Guide. Japan’s Strangest Livestream | Nasubi | A Life of Prizes // YouTube [Online source] URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k_o8v88nkKc (date of reference: 17.12.2021)

REFERENCES

Andrejevic, M. (2004) “The webcam subculture and the digital enclosure” in: Couldry, N., McCarthy, A., eds. Mediaspace: Place, scale and culture in a media age. Routledge

Baudrillard, J. (1987). The ecstasy of communication.

Bridges, A.J., Wosnitzer, R., Scharrer, E. Sun, C., & Liberman, R. (2010). Aggression and sexual behavior in best-selling pornography videos: A content analysis update. Violence Against Women, 16, 1065–1085.

Fritz, N., Malic, V., Paul, B., & Zhou, Y. (2020). A descriptive analysis of the types, targets, and relative frequency of aggression in mainstream pornography. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(8), 3041-3053.

Kim, Y. (2021). Eating as a transgression: Multisensorial performativity in the carnal videos of mukbang (eating shows). International Journal of Cultural Studies, 24(1), 107-122.

Perales Bazo, F. (2011). La realidad mediatizada: el reality show. Comunicación: revista Internacional de Comunicación Audiovisual, Publicidad y Estudios Culturales, 1 (9), 120-131.

Vera-Gray, F., McGlynn, C., Kureshi, I., & Butterby, K. (2021). Sexual violence as a sexual script in mainstream online pornography. The British Journal of Criminology, 20, 1-18.

Žižek, S. (1998) Cyberspace, or, How to Traverse the Fantasy in the Age of the Retreat of the Big Other. Public Culture, vol. 10(3)

Žižek, S. (2008). Violence: Six sideways reflections.

Žižek, S. (2019). The sublime object of ideology. Verso Books.

McLuhan, M., & MCLUHAN, M. A. (1994). Understanding media: The extensions of man. MIT press.

Луман Н. Тавтология и парадокс в самоописаниях современного общества / Пер. Филиппова А.Ф. // Социо- Логос. No1, 1991. С. 194-218.